Results from the Hubble Cycle 26 TAC

The Problem with the Hubble TAC

If you are a research group that wants time to observe with the Hubble Space Telescope (HST), you need to submit a proposal to the Telescope Allocation Committee (TAC). Once a year, the TAC receives, in a usual cycle, proposals for 4-5X the amount of time it actually has to offer [1]. Hence, the allocation process.

But the allocation is not perfect because it, as with science in general, is a human endeavor; as much as some would like to deny it, TACs are a subjective process. Studies have shown that if two different panels review the same set of proposals, they usually only agree on about 50-60% of them [3]. Even more disconcertingly, the HST TAC consistently under-accepts proposals with female PIs, on average about by about 5% compared to proposals with male PIs [3], which comes out to a 6-10 proposal offset [4]. If no systematic bias was present, we would expect this percentage to fluctuate, some years favouring female PIs and other years favouring male PIs. But in the ten years studied by [3], the proposals with female PIs were under-accepted every time.

A more detailed look at the data (done by [3]) reveals trends which may or may not be meaningful, some more surprising than others. The offset is unaffected by the gender distribution of the review panel or the geographic origin of the proposal. The rates for recent graduates are more comparable; senior female PIs bear the brunt of the selection bias. The relative number of proposals with female PIs is increasing over time (due to demographic shifts), but the Large proposal category is disproportionately dominated by male PIs. Stars and cosmology have the worst acceptance offsets, while galaxies are more equal. The higher the proportion of senior members on the panel, the worse the acceptance rates for proposals with female PIs, while panels with junior members tend to have smaller offsets.

The most important outcome of this study, though, is this: the offset is only slightly present before the panel discussion phase of the proposal review, and suddenly spikes in the final selections by the TAC [3]. So what’s happening in these panel discussions that’s causing the discrepancy?

Attempts at a Solution

Before proposal Cycle 21, the name of the PI was all over a proposal submission: in the name of the file and in the first words on the proposal itself. In addition, every member of the proposal was identified by both first and last name, allowing the reviewers to assume (explicitly or implicitly) the gender and ethnicity of the PIs and co-Is.

Once the Space Telescope Science Institute realized that there was systematic bias pervading their review process, they took some small steps to try to fix the issue. In Cycle 22-23, they removed the PIs name from the filename and the first page, and identified the PIs and co-Is by first initial and last name only (removing the first names). In Cycle 24-25, they listed the authors alphabetically, still without first name, with no PI identified.

These measures didn’t solve the problem, as shown in the figure below.

Diagnosing the Ongoing Issue

According to the data, the remedial measures in Cycles 22-25 didn’t work, and we knew that the problem had to be in the panel review itself. So STScI had Dr. Stefanie Johnson of the Leeds School of Business at the University of Colorado and her graduate student Jessica Kirk sit in on the HST Cycle 25 TAC, with an eye on applying the results to the first set of JWST proposals (sad). The results of the report were surprising in illuminating the depth of the problem, if not the breadth.

According to their report, almost 50% of the discussions in the HST Cycle 25 TAC included a focus on personnel that detracted from the science [2]. Overheard statements from the panel reviews included “He [the author] is very well qualified” and “My group has benefitted a lot from previous work from this team” [5]. The panel members even pulled up research articles and noted citation counts from the groups submitting the proposals [5].

With this new information, STScI formed a Working Group on Anonymizing Proposal Reviews (APR) to make changes for Cycle 26.

A New Approach: Dual-Anonymous

This year’s TAC was a little different. It was four months later than usual (causing the submission of 489 proposals and a skyrocketed oversubscription rate of 12:1 [1]), it focused on bigger proposals, and it implemented a dual-anonymous system proposed by the APR Working Group.

The dual-anonymous system means that not only do the proposers not know who their reviewers are, but the reviewers don’t know who their proposers are. This is the first time this has been done for a large-scale proposal in the physical sciences [1]. The Working Group also had a few specific suggestions to make the process run as smoothly as possible. They added “levelers” to the discussions: personnel whose job it is to step in if the discussion veers away from the science itself [1]. They also added a “Team Expertise and Background” section that is only made available after the rankings are finalized (in order to preserve anonymity). At the stage where the TE&B section becomes available, proposals can be rejected if it’s determined that the proposers don’t have the necessary resources and experience to carry out the proposed science. But the rankings themselves cannot be changed based on the new information, except to pull proposals out of the list if they don’t seem feasible [1].

Some criticisms of the new system, and replies that address them, are shown below:

“This won’t work for astronomy because the field is too small – we’ll be able to tell who it is anyway!”

Studies from other fields suggest that the PIs identity is still secret 60-75% of the time [2]. And even if it isn’t perfectly anonymous, it shows a dedication to improvement and equity.

“How will we properly assess if the authors have the resources and experience they need to carry out the proposed science?”

This is a fair criticism, and was the main reason that the final TE&B stage in the above review process was added.

“Won’t this make it harder for me to get time?”

The same amount of time is being given and thus, the same amount of proposals are being funded. It works the same as always: think of a great idea then write a great proposal [2]. You’ll only see a change in your outcome if you were coasting on your privilege and reputation instead of your actual science in the first place.

Results of the Dual-Anonymous System

This cycle’s TAC met in October 2018 to try out the new system. Only one proposal was thrown out because it was anonymized incorrectly – it seems that the proposal writers adapted well to the new guidelines [1]. The panelists said it was “almost liberating” to focus on the science instead of the people, and the “levelers” only rarely had to intervene [1]. In the end, no proposals got rejected during the TE&B phase: all highly-ranked proposals were still considered feasible after their groups’ expertise and resources became known [1].

The topics of the selected proposals were as wide-ranging and interesting as ever and included gravitational wave follow-up, constraining cosmic distance scales, Jupiter’s magnetosphere, habitability near Proxima Cen, mass outflows from Betelgeuse, and mapping the Local Group.

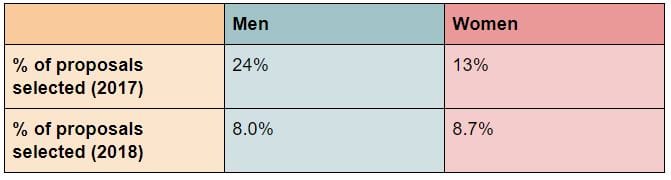

So did the dual-anonymous system actually diminish the acceptance gap? I’ll let the numbers speak for themselves.

Takeaways and the Future of TACs

It has been shown in other fields that dual-anonymity decreases bias related to gender, institution, prestige, age, and nationality [2], and the graphs above show first-impression evidence that this is true in astronomy as well. Given these preliminary results, the Space Telescope Users Committee is recommending that the changes to the process stay – the next TAC meeting (June 2019) will keep the same dual-anonymous format [1]. Even more excitingly, the success of this program might make the process standard for the JWST TACs as well [2]!

The final success of these procedures will be judged on other factors as well as just pure acceptance rate: productivity, diversity, gender balance, number of new proposers, and the success rates of junior and senior PIs will all be examined in the future [2]. The final impact may take a few years to determine, given our reliance on publication and citation rates as proxies for success.

My Thoughts

Knowing this, we can’t just be happy that the future of astronomy proposals look more equal – we also need to extrapolate back into the past. The number of accepted proposals was a statistic that supposedly marked an “objectively” good researcher, but now we know that the number is implicitly biased. Faculty hiring committees, for example, will now need to take this into account when comparing applicants. Although many of us knew that this problem existed before now, having the results from Cycle 26 just makes it crystal-clear that we were not comparing scientists on a level playing field.

As a side note (this is basically a “Discussion” section now), it has been shown that men and women take advantage of optional dual-anonymous review for Nature journals at the same, low rates [6]. This may be surprising on the surface, but can be attributed to a perception that the deliberate selection of a dual-anonymous procedure option could backfire on the author [6]. The solution to this problem is to stop putting the onus on the authors who are already disadvantaged by the system and to make dual-anonymous procedures standard in science.

I hope it’s pretty clear why this all matters, but let’s be explicit. Gender diversity leads to greater innovation. The dual-anonymous system focuses attention on the quality of the science and creates more equal opportunities for HST [2]. If you are still not convinced, Reid calls the constant acceptance offset a “canary in the coalmine” [4] that proposals are not being compared on their actual merits: that the process is riddled with implicit biases that undermine the goal to produce the best science. We ignore the canary at our peril.

References

[1] Reid, N. (2018). Hubble Cycle 26 TAC and Anonymous Peer Review. STScI Newsletter, 35(4). Retrieved December 16, 2018, from http://www.stsci.edu/news/newsletters/pagecontent/institute-newsletters/2018-volume-35-issue-04/hubble-cycle-26-tac-and-anonymous-peer-review.html

[2] Garnavich, P., Johnson, S., Lopez-Morales, M., Prestwich, A., Richie, C., Sonnentrucker, P., . . . Reid, N. (2018, May 14). Recommendations of the Working Group on Anonymizing Proposal Reviews. Retrieved December 16, 2018, from https://outerspace.stsci.edu/display/APRWG

[3] Reid, N. (2014). Gender-Correlated Systematics in HST Proposal Selection. Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 126(944), 923-934. doi:10.1086/678964. https://lavinia.as.arizona.edu/~gbesla/ASTR_520_files/Reid2014_HSTStats%20copy.pdf

[4] Reid, N. (2017, December). HST Proposal Demographics. Presentation for the Anonymizing Proposal Reviews Working Group. STScI. https://outerspace.stsci.edu/display/APRWG?preview=/11665517/11667175/proposal%20statistics.ppt

[5] Johnson, S. (2017). Going Blind to See the Stars: Removing PI Name Decreases Gender Bias in Hubble Proposal Ratings. Presentation for the Anonymizing Proposal Reviews Working Group. STScI. https://outerspace.stsci.edu/display/APRWG?preview=/11665517/11667176/Hubble%20Presentation.pptx

[6] Enserink, M. (2017). Few authors choose anonymous peer review, massive study of Nature journals shows. Science. doi:10.1126/science.aaq0322. https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2017/09/few-authors-choose-anonymous-peer-review-massive-study-nature-journals-shows

[7] Leitherer, C. (2018, November 13). Cycle 26 Summary and Plans for Cycle 27 [HST TAC Summary Document]. http://www.stsci.edu/institute/stuc/fall-2018/HSTTAC.pdf